Many students often ask me: Hey David, how to learn Mandarin Chinese fast? Maybe in 3 or 5 days?

Me: Are we talking about A.I. or something?

Questions like this tells me that there are some misconceptions about learning a language. Since there are too many “fast-food” language-learning advertisements around us, we are easily misguided into believing that learning a new language can`t be easier and faster. I can confidently say that learning Chinese as a second language is not a three or five-day thing. Of course, it is not considered mastery if you just know “你好(nǐ hǎo)”, “谢谢(xiè xie)” and “我很好(wǒ hěn hǎo)”. Nevertheless, you shouldn’t be afraid of learning Mandarin Chinese. There are ways to make your learning more efficient and faster through a more logical method. Here are seven steps that will help you how to learn Chinese fast.

1. Do basic research

There is a Chinese saying, “磨刀不误砍柴工”, which means “the more the preparation, the faster work gets done.” To begin with, you need to do some basic research about your target language, Mandarin Chinese. There are thousands of articles and videos that introduce the Chinese language. You should read and view these to know the language’s general history and how it works. Several questions that could arise are:

Why are there traditional and simplified Chinese characters?

Which one should I learn?

Why are Chinese characters made of strokes and not letters? What is the history behind this?

What is the difference between Mandarin and Cantonese?

Are 汉语(hànyǔ), 中文(zhōngwén) and 普通话(pǔtōnghuà) the same?

What is your learning goal?

How long would you like to spend on learning this language?

……

During your research, you may find the answers to these questions and decide the right and suitable way to go to learn the language.

2. Lay a solid foundation

I`m often asked if learners can just skip the boring beginning part and learn the “useful” and “practical” conversation part. Well, if you are in a hurry and just want to grab several basic greetings to warm up the meeting with Chinese people, then yes, you can just imitate some greetings directly. However, these greetings won`t take you far. If you are a serious learner who wants to have a longer and more meaningful conversation with Chinese people, take some language tests, or live in China, a solid foundation of the Chinese language will make your learning easier and give you fewer obstacles. In other words, you can learn Chinese faster and better. All in all, a good beginning is half the battle.

So, what the is the foundation of Chinese? The first foundation should be the Pinyin system. It is definitely necessary and never too late to make sure your pronunciation is correct, but how? The answer is to start from the basics, such as the tone, the final, the initial, the spelling rules, etc. I wrote a complete pronunciation guide which should give you a general idea about how to best learn Chinese pronunciation. After this stage, you can spell all pronunciation of Chinese characters out automatically with no hesitation. Good pronunciation will make your communication with Chinese people more smooth without any misunderstandings when speaking.

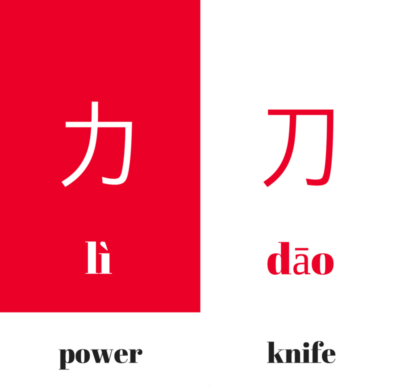

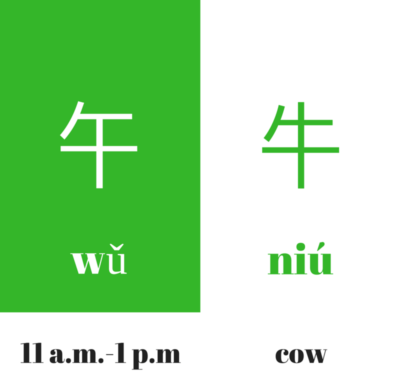

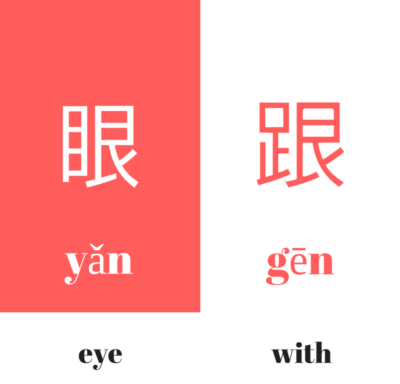

Besides pronunciation, another foundation is learning Chinese characters. You may wonder why Chinese characters are necessary. Are they worth learning? Yes, you can learn some basic sentences even if you don`t know any Chinese characters. But with that method, you need to make sure you have a very good memory and be immersed in an everyday Chinese speaking environment, so that you will not forget the content you learned through listening and repeating. But without a doubt, you will definitely lose the ability to read and distinguish many Chinese homonyms. Without knowing Chinese characters, you have no way to be an advanced or even an intermediate learner. If you learn simple characters from the beginning, you may find it`s not that difficult to learn especially when you get past the first stage. There are four main Chinese Characters types, and learning the basic characters stroke by stroke will lay a good foundation and benefit your future learning.

3. Master the knowledge points and link them together: make a logical net

Whenever we speak of knowledge points, grammar comes to our minds immediately. It seems there are many grammar points to learn during the whole language learning process. However, as I always claim, Chinese grammar is really not as difficult as you think. We don`t even need to change the tense and gender in Chinese, unlike in other languages. Using English speakers as an example, you should know the difference between English and Chinese first, then this can give you a better overview of the target language. And if you have learned some rules on the periods of time, you can summarize most of the grammar points into one sentence structure:

Subject + time preposition + Time + location preposition + Location (from the biggest to the smallest) + how (can be adverb or a phrase containing a preposition.) + Verb + time duration + indirect object + Object

With this structure, you can solve many Chinese grammar problems. The process you learn to summarize those grammar points is the key to link them together and make a whole knowledge net. What you need to do is put the new point in the right position of the grammar net.

As you can see, the picture above also shows us a net for learning vocabulary. You can start with a topic that interests you such as shopping or playing sports. Write down this main topic in the middle of a big sheet of paper. Add branches from the main topic and use related phrases or words as the titles. This method also works when learning Chinese characters. It`s a fun and easy way to start building your vocabulary of Chinese characters through a continuous and vivid approach.

4. Sharpen your learning method

How to learn Chinese fast? Choosing the right and suitable way for you to learn a language can make you learn faster. Generally speaking, there are two ways to learn: self-learn, or learn with a tutor. No matter which way you choose, the method and tools of each way are important to know.

Self-learning

As a self-learner, the ability to collect high quality learning materials and resources is necessary. The development of internet technologies has been constantly changing the process of learning a foreign language, and we should use the maximum available online tools to do so. A complete resource website can help a lot, such as DigMandarin. You can find all Chinese learning skills, materials, resources, and even courses there. It is quite convenient to have it all in one digital place. There are also lots of online libraries where you can browse textbooks for free. If it fits your need, you can buy them on Amazon or other online bookstores. When you drive or are stuck in traffic, you can listen to some podcasts to strengthen your Chinese listening, such as Chinese Class 101 and ChinesePod. At home or at the office, you can also attach some individualized flashcards somewhere conspicuous to remind you of some related vocabulary every now and then. During your own study time, you can focus on a selected textbook or on an online Chinese video course. For sure, more study APPs have come out now. You can try various APPs and take advantage of your learning time. If you use these tools properly, you can definitely control your learning better.

Learn with a tutor

“A professional Chinese tutor can save you quite a lot of time if your goal is to learn Chinese fast, primarily because a Chinese tutor can offer you one-on-one instruction that is tailored to meet your specific needs and abilities.” At your own convenience, you can choose an online or an offline Chinese school. Online learning is quite convenient for learners who have requirements about time and place. No matter where you are, you can start to learn anytime. Without the limitation of time and place, offline local language school is your best choice. Face to face communication can boost your passion for this language and make you more Chinese speaking friends. All in all, a professional tutor can save you lots of time to achieve your goal.

5. Immersion learning: make your own language environment

Language is a kind of communication tool. If you don`t use it, you will obviously lose it. Sometimes, no letting-down in your learning is also a sign of progress. Therefore, we need to keep activating our senses for reading, listening, speaking, and writing. Find your own way to make an environment for the Chinese language and immerse yourself in it.

“Living in” the target language is the ideal way to acquire it amazingly fast. It pushes you to keep involving yourself fully with the language. Thus, the best way is to try to live in China for a period of time, if you can. Of course, don`t just be with non-Chinese speakers everyday. Make more Chinese-speaking friends! Those everyday first-hand local Chinese language terms and sayings are not found in the textbook.

But how about if you can`t be in China? Then you`re lucky if you happen to have Chinese speaking family-members, classmates, colleagues, or neighbors around you. It`s very easy to develop a Chinese-speaking environment. I know some of you are embarrassed to trouble others, but what you can do is call all the Chinese learners of your community together and make a Chinese corner. You can then all learn together! Or you can also find someone to learn with as your language partner.

As the saying goes, “interest is the best teacher”. Even light-hearted activities can also help you immerse in the language. You can watch Chinese TV series, Chinese movies, or listen to Chinese songs. You can enjoy the content and learn the language at the same time. This method works all the time.

6. Use it as much as you can

As a second language learner, I know Chinese students have a common problem, which is we often avoid speaking the target language out. Many Chinese are too shy to dare making mistakes, thus we just keep silent. Of course, we can`t acquire the language very well since we rarely use it in real life. Therefore, I keep telling my students and audiences, use Chinese as much as you can! Don’t be shy or afraid. Regardless of output, it`s not only about speaking, but also writing. Speaking and writing in Chinese can help you organize your knowledge and acquire it very well. Regarding input, listening and reading are the common methods to learn more of the target language. Many foreigners live in Shanghai or Beijing for several years, but they can only say 你好 and 谢谢. Why? Because they never use Chinese, only their daily social languages. It`s ok if they don`t even want to learn this language. But for you, a serious Chinese learner, just open your mouth and ears. Use the target language in your daily life, so that you know which part you need to improve or refresh.

7. Strengthen the weak parts and the useful parts

Setting an achievable goal is an effective method of study. For example, you can try to take some Chinese language tests like HSK or HSKK. The test itself is not the aim. Rather, we can get a direct and clear understanding of your Chinese level through the test. At the very least, your listening, reading, and writing skills can be tested by taking HSK. The results of each part are quite clear and objective. Then you would know which parts you need to improve on. Based on the Cannikin law, it is only if we strengthen the weak parts can we step forward to the next, higher level.

Besides the weak parts, we also need to strengthen the parts useful for us. For example, to a business Chinese learner, it`s really not necessary to learn many classroom expressions. After the foundation stage, we can start our target part. After all, language is a tool which we should use frequently. So now we can be back to our first tip: ask yourself why you want to learn Chinese? Don`t get lost in the language ocean. Always keep your focus on your language goals.

Strengthening these parts can not only encourage you, but can also help you learn Chinese as fast as you want.

Welcome to have my face to face lesson on http://www.verbling.com/teachers/dawei ! 🙂