If you are only just starting out learning Chinese characters you may have already come across some Chinese characters that, to the inexperienced eye, look exactly the same. It’s different to get over the idea that they are different and that it is possible, by following some simple rules, to distinguish between these characters.

How to Learn Chinese Characters Through Context

If you have read some of our other articles, or have been studying Chinese for a while, you may have started learning Chinese with Pinyin. Although there are several drawbacks to only studying Pinyin as a method of learning Chinese, it can be used at the beginning of your studies to not only perfect your Chinese pronunciation, but to also learn the different pronunciations for one single character.

Sometimes, one Chinese character may have multiple pronunciations and meanings. For example, the character 好 you may already know means ‘good’ with the hǎo pronunciation. However, this character has a second, although less common pronunciation, hào. If you are reading Chinese, how do you know whether the character is the hǎo or the hào version of the character? Most of the time, the answer simply lies in the context or nature of the conversation. For characters like this, when one pronunciation is used much more than the other, the context of the conversation would allow you to choose the hǎo pronunciation.

For example, if you were to see this sentence, 这种菜很好吃。(zhè zhǒng cài hěn hǎo chī.) it would be pretty difficult to mistake the pronunciation or meaning as hào, meaning ‘to be fond’.

How to Learn Chinese Characters With Bigrams

Sometimes, there are also characters that have 2 or more pronunciations that are frequently used, and context may not be sufficient enough to know which pronunciation to use.

Let’s look at the character 还. 还 has two pronunciations and two meanings. The first pronunciation is (hái) meaning ‘still’ and (huán), meaning ‘to return’.

If you have learned this character, you may know some of the common ways in which the character can be found in a sentence. In the sentence below, for example, the 还 (huán) character is followed by 给 (gěi) meaning ‘to give’. Even if you have never learned this combination of characters before, you might be able to guess what 还给 (huán gěi) means, if 还 (huán) is ‘to return’ and 给 (gěi) is ‘to give’.

他给她打开门锁,并把钥匙交还给了她。(tā gěi tā dǎ kāi mén suǒ, bìng bǎ yào shi jiāo huán gěi le tā.)

He unlocked her car door, and gave her back the key.

还给 (huán gěi) is an example of a 2 character combination that we call a bigram. Bigrams can be found in many languages, including English. They can be letters or words that are commonly found together to create a specific sound or meaning. In this case, the bigram 还给 (huán gěi) means ‘to give back’. It would be less likely (although not impossible) to find the 还 (hái) pronunciation of the character in proximity to the 给 (gěi) character especially based on the context of the sentence. Deciding which character to choose in this case is a combination of context and learning bigrams.

Learning bigrams instead of struggling with single characters is a way in which you can learn to distinguish between characters that look very similar. There are some characters that just plain look alike. They may have an extra line, or an additional sticky-out bit, but to the beginner, they can quickly be mistaken for the wrong character. This is why learning bigrams, especially as a beginner of the Chinese language, can reduce such mistakes, because you are not focusing on one single character, but on the common 2 character combination.

If you get stuck when reading a character in a sentence look to the next character. If you’re studying bigrams, chances are the second character will remind you of the first character.

Below are some examples of character that look similar, but because of the common bigrams that they are found in, will make it easier to tell them apart.

In this next section, I will refer to specific character ‘strokes’ or lines that are used when writing characters. You may wish to refer back to our article, Chinese Character Strokes, but here is a quick review of the ones I will mention most often:

横 (héng) – horizontal line

竖 (shù) – vertical line

撇 (piě) – downward curving stroke to the left

捺 (nà) – downward curving stroke to the right

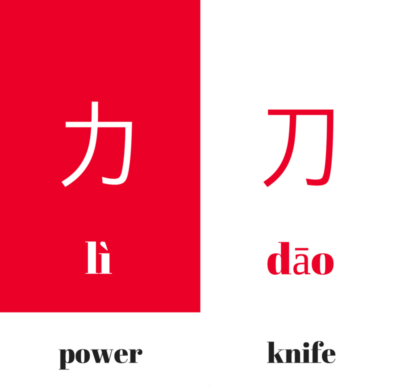

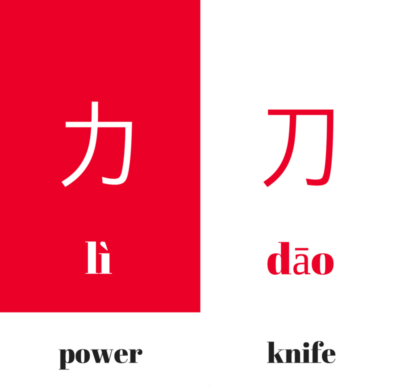

力/刀 (lì/dāo) power/ knife

Difference: The balance of these characters is slightly different, as the 刀 (dāo) character is larger and takes up the whole ‘space’. The 横 (héng) stroke of the 力 (lì) character should begin lower, allowing for the downward curving stroke, known as 撇 (piě), to begin above the horizontal stroke.

Examples of 力 (lì):

努力 (nǔ lì) – to try hard

压力 (yā lì) – pressure

Examples of 刀 (dāo):

刀子 (dāo zi) – knife

剪刀 (jiǎn dāo) – scissors

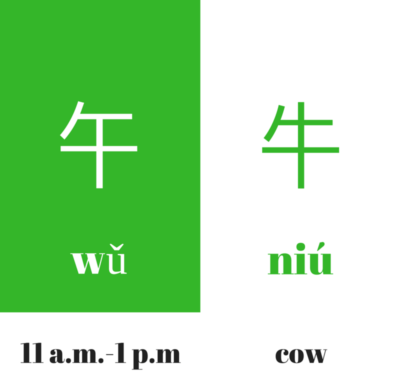

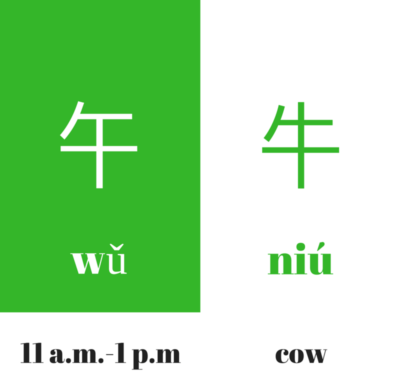

午/牛 (wǔ/ niú) 11 a.m.-1 p.m/ cow

Difference: The tip of the vertical stroke on the 牛 (niú) character, known as 竖 (shù), begins slightly above the first horizontal stroke, 横 (héng).

午 (wǔ) is rarely used on its own, and often found in time phrases like in the following:

Examples of 午 (wǔ):

下午 (xià wǔ) – afternoon

上午 (shàng wǔ) – morning

Examples of 牛 (niú):

牛肉 (niú ròu) – beef

牛奶 (niú nǎi) – cow’s milk

已/己 (yǐ/ jǐ) already/ self

Difference: Two of the more difficult characters to distinguish between, 已 (yǐ) and 己 (jǐ) are almost identical apart from a tiny extra line in the 已 (yǐ) character. The 竖 (shù) stroke begins above the second horizontal stroke.

Examples of 已 (yǐ):

已经 (yǐ jīng) – already

早已 (zǎo yǐ) – a long time ago

Examples of 己 (jǐ):

自己 zì jǐ – oneself

知己 zhī jǐ – to know oneself

How to Learn Chinese Characters with Mnemonics

With some characters, creating mnemonics can help with distinguishing between similar looking characters. A mnemonic can be a story or pattern of letters that can help you to remember something longer or more complex. A Chinese character mnemonic can help remind you of as many elements of the character as you want, meaning, tone, pronunciation etc.

买/卖 (mǎi / mài) buy / sell

A simple mnemonic to distinguish between 买 (mǎi) and 卖 (mài) is that if you ‘sell’ 卖 (mài) something you will receive money (maybe ten 十 (shí) ?). The character 十 (shí) can be seen added to the top of the 买 (mǎi) character to make 卖 (mài).

You can apply a mnemonic to any character to remember it. You can visit our Online Dictionary and view existing mnemonics or even post your own ideas.

How to Learn Chinese Characters with Radicals

Radicals are the ‘building blocks’ of Chinese characters. They are most often on the bottom or the left side, and indicate the ‘meaning’ of a character. For example, the character 口 (kǒu) is also used as a radical and means ‘mouth’. Therefore, the radical 口 (kǒu) is often found in words that relate to the mouth, such as 叫 (jiào), meaning to shout or 吃 (chī) meaning to eat. In order to learn Chinese characters properly, it’s a good idea to start acclimatizing yourself with some of the basic radicals.

You can learn about some of the more common Radicals here. You can find the radicals for all the characters you learn by checking them in the Written Chinese Dictionary, both online and in themobile app. Just search for the character and you will a ‘Radical Breakdown’ for that character.

For a more comprehensive list of radicals, take a look at the radical feature in our Written Chinese Dictionary app.

Radicals can be one of the best ways to distinguish between Chinese characters, especially as the right hand side of the character often refers to (but not always) the pronunciation of a character.

Let’s look at these characters for example:

线/钱 (xiàn/qián) line/money

Both characters contain the same part: 戋 (jiān). It would be very easy to mix up these characters, if you did not pay attention to their specific radicals.

Both characters, 线 (xiàn) and 钱 (qián) , take their pronunciation from 戋 (jiān) that we see on the right hand side. The meaning of the first character 线 (xiàn), is ‘line’ or ‘thread’ and is dictated by the radical on the left hand side, 纟(sī), which represents a bolt of silk. The second character, 钱 (qián), has the radical for ‘gold’ ,钅(jīn) which tells us that the meaning of the character is ‘money’ or ‘coins’.

Here are some other examples of characters that look alike, but can be differentiated by their radicals.

那/哪 (nà/nǎ) that/how

The character 哪 (nǎ) features the 口 (kǒu) radical, meaning mouth. The 口 (kǒu) radical, as mentioned above, is often used for characters relating to the mouth. It is also used in some question words including 吗 (ma) and 哪 (nǎ).

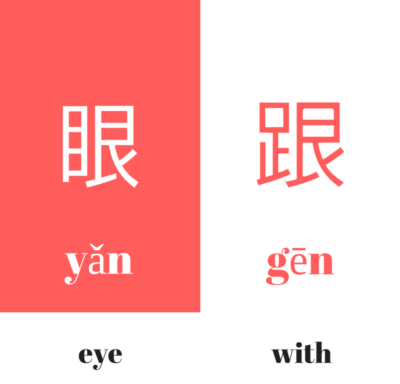

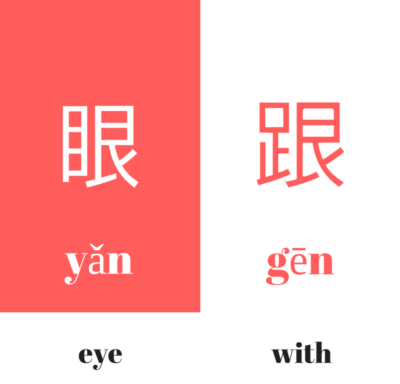

眼/跟 (yǎn/gēn) eye/with

The right hand part of the character is 艮 (gèn) and provides the pronunciation for 眼 (yǎn) and跟 (gēn). The radical for the 眼 (yǎn) character is 目 (mù), meaning eye. The radical found in the跟 (gēn) character is 足 (zú) or foot. The foot radical is used here because the full meaning of 跟 (gēn) is ‘close behind’ or the ‘heel’ of a foot.

Exercises

If you want to test your character recognition, complete these simple exercises and we’ll post the answers later!

1. Add another stroke to the 日 (rì) character to make new ones (hint: you can make around 9 characters).

2. Find the ‘wrong’ character in the sentences.

a. 我己经吃过饭了。(wǒ jǐ jīng chī guò fàn le.) I have finished the meal.

b. 下牛去看电影好吗? (xià niú qù kàn diàn yǐng hǎo ma?) How about going to the cinema this afternoon?

c. 妈妈没有告诉我他去哪儿了。(mā ma méi yǒu gào su wǒ tā qù nǎr le) Mom didn’t tell me where she was going.

Welcome to have my face to face lesson on http://www.verbling.com/teachers/dawei ! 🙂